- in Book Excerpt , Production , Recording by Bobby Owsinski

Ken Scott On Working At Trident With John Lennon And George Harrison

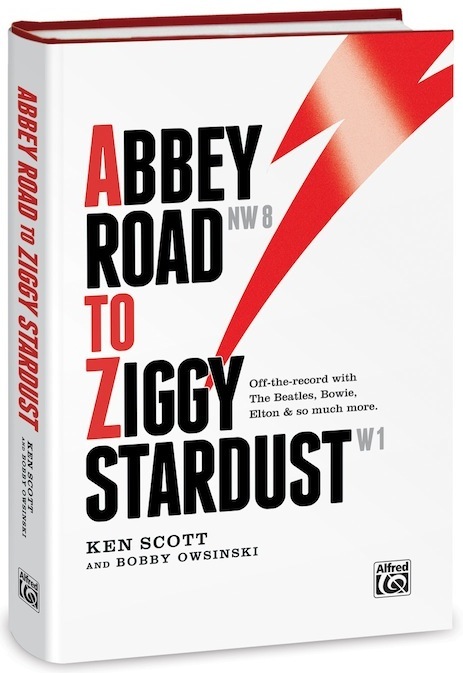

In an excerpt from his autobiography Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust (which I was lucky enough to co-write), legendary producer/engineer Ken Scott describes what it was like to work at the famous Trident Studios in London with former Beatles John Lennon and George Harrison.

“Trident Studios was located at 17 St. Anne’s Court, just off Wardour Street in the heart of the Soho district of London. It was originally constructed in 1967 by drummer Norman Sheffield and his brother Barry, who both managed the studio, although when first opened Barry was also one of the only two engineers there. I was originally brought into the fold because Barry wanted to spend more time as the studio manager and get out of engineering because of all the long hours that entailed, which as it turned out, didn’t happen quite as soon as everyone had planned.

The facility was located in a large five story building that had originally been a printing works and was supposedly on a burial site for the victims of the Great Plague of 1665. As you entered through the heavy glass and wood door you were confronted by stairs leading down to the studio, and if you turned right you were in the reception area. Once in reception you couldn’t help but notice another very heavy wood door that led into the control room, not the most convenient arrangement for the musicians, as every time they wanted to hear something back they had to climb those stairs and hike through reception, only to be greeted by another three stairs to bring them in front of the mixing console. Now traipsing all that way up was just the beginning. If another take was needed the thing that happened all too frequently was that in the excitement of the moment the artist, me too on occasion, would jump down those three stairs and collide heavily with the door jamb. A severe headache quickly ensued, a not particularly good start to getting that perfect take.

The next floor up, reached by either stairs or lift, was a small lounge, the machine room where all the studio tape machines were housed and, shortly after my arrival, the mix room and overdub booth. On the second floor (third for Americans) was a screening theater. Wardour Street was home to many film companies at that time and rather than putting all their eggs in the record business basket, Barry and Norman thought that after coming to what was a particularly posh viewing room for the time, the film execs might be interested in using the studio to record the music for their films. It never actually happened that way, although it really didn’t matter as the studio was constantly working around the clock anyway. On to the third floor, where maintenance and eventually cutting resided, then on the top floor was the kitchen. I use the term “kitchen” very loosely as it was geared more towards the making of tea and coffee and anything that could fit into a small toaster oven rather than a gourmet treat.

After having spent the better part of five years at EMI, the difference in culture could not be missed. EMI studios had a certain coldness to it, and felt very much like a place where you went to “work.” Certainly not the kind of place you’d want to go to if you weren’t actually working. Trident however had this great feeling of camaraderie, everyone working together toward the same end, and it soon became a place to hang out. People would specifically come there even if they weren’t recording. It was so much more laid back, and of course, you didn’t have to wear suits and ties like everyone did at the very proper EMI.

There were a couple of work related things for me that were different from EMI. The Beatles way of working seemed to have become the norm throughout the recording business, and so sessions were no longer booked in those union-dictated three hour time blocks. They generally started in the early afternoon and were open-ended. On occasion we’d have a brief morning session, but they tended to be more with session musicians than bands.

Another major difference for me was that there was only one maintenance guy there at any time, instead of the slew of them I was used to over at Abbey Road. That meant that from time to time we had to align our own tape machines and always had to set up our own sessions.

The original engineers at Trident were Barry and Malcom Toft, who was also good with electronics and went on to design the studio’s famous consoles. Roy Thomas Baker came a little after me from Decca, where he’d been a tape op and engineer. No one can quite remember when Robin Cable came along, but soon it was the three of us that were doing the majority of the work. The people in charge of putting us on sessions learned pretty quickly that we each had our own genres that we did best in. Roy was put on more of the heavy and outrageous type of things like Ginger Baker, Zappa or John Entwhistle. Robin was the more folky or orchestral type of things, and I was somewhere in the middle.

“Give Peace A Chance”

Even though I was now at a new studio, my connection to The Beatles still remained strong. I’m not sure what my first project at Trident was, but right after I started John Lennon brought in his first solo single, “Give Peace A Chance,” for me to mix. The session was booked in by Apple, but whether it was because I was there, I have no idea.

“Give Peace A Chance” was a live four track recording done by Andre Perry (who later built the excellent Le Studio in Quebec) in a hotel room in Montreal and who later bounced it to an 8 track machine and added four more tracks of vocals. There’s a repeat on one of the tracks where someone was just hitting something, and as the song goes on the repeat is pushed up in the mix higher and higher, which must have come from John saying, “More, more,” which was typical of him. I had learned from my previous experience with “Hey, Jude” about the sound of the monitors, so I strapped a couple of graphic equalizers across them and rolled off the high end so the sound coming out of them was more realistic, and the result is the record that you’re familiar with today.

All Things Must Pass

George Harrison came by about a year after my start at Trident to do the overdubs on his first solo album All Things Must Pass. The record was started at EMI (the name still wasn’t changed to Abbey Road Studios at this time) on 8 track with Phil McDonald engineering. It was very quickly obvious that they needed more tracks so they moved to Trident because of our 16 track machine. Good old EMI, always late with the technology. The producers on the album were George and Phil Spector, even though Phil was never around for any of the overdubs. We were graced with his presence a little bit when we were mixing though.

By the time I got the project, there had been some overdubs recorded already, which is probably when they decided they needed more tracks. The basic track varied for each song but generally it was drums, bass and all of the acoustic guitars, but there was also some pedal steel by the famous Nashville session player Pete Drake, and sometimes brass on a few of the songs. We recorded the vocals, electric guitars, additional brass, orchestra and some keyboards at Trident.

I asked him, “What sound do you want?” and he said, “I don’t care.” My job was to play the arpeggio because everything got split into chords and arpeggios. I turned up early for the session and there was a few people milling around, and one by one all these people began to arrive very casually. It was Alan White on drums and Klaus on bass, one of the Badfinger guys on guitar, lots of people on percussion. Suddenly Ringo shows up and there’s a second set of drums, then Eric Clapton on guitar, and the thing built up and up and up. After we put down the first track and had a listen. George asked to listen what they’d done the night before, then asked to put Eric’s guitar up a bit. Phil said, “I can’t,” because everything had been mixed directly to two tracks live even though we were using an 8 track machine. There was a bit of a dust up between George and Phil over that, but Phil said to him, “If you want me to produce it, this is what I do.”

Chris Thomas (on playing Moog synthesizer on the basics of All Things Must Pass)

It’s hard to know who played on which tracks on the album because it was never documented. Unfortunately, no one seems to remember much either. When we were doing the reissue of ATMP in 2001, George wanted to put extra material like interviews on it, so one afternoon I went around to Ringo’s L.A. home and after I set up a small recorder in the garden I was ready to ask him some questions. First question: “What do you remember about doing All Things Must Pass?” He looked at me blankly and said, “Did I play on it?” Unfortunately that seems to be an all-too-typical answer. George didn’t remember who played on what song either.

We worked on ATMP for quite a while, having no sense of time, for I guess what amounted to about two months including mixing. George did so much himself. Virtually all of the backing vocals were George, like what you hear on “My Sweet Lord.” We’d do four or six tracks of him singing a line and I’d bounce all of those down to one track. Then he’d do a harmony several times and I’d bounce those to another track. They we’d bounce those two together at the same time as we were doing yet another backing vocal. It was painstaking, but it sounds amazing in the end.

When it was time to mix, normally George and I would begin at about 2:30 or 3:00 in the afternoon. We’d spend some time getting it to where we were both happy, then Phil would come by for maybe an hour. He’d pass his comments, we would mull them over, and usually make the changes he wanted. Then off he would go and we’d finish it off and come back the next day to start all over again.”

You can read more from Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust and my other books on the excerpt section of bobbyowsinski.com.

Sorry, but comments have been disabled due to the enormous amount of spam received. Please leave a comment on the social media post related to this topic instead.