- in Production by Bobby Owsinski

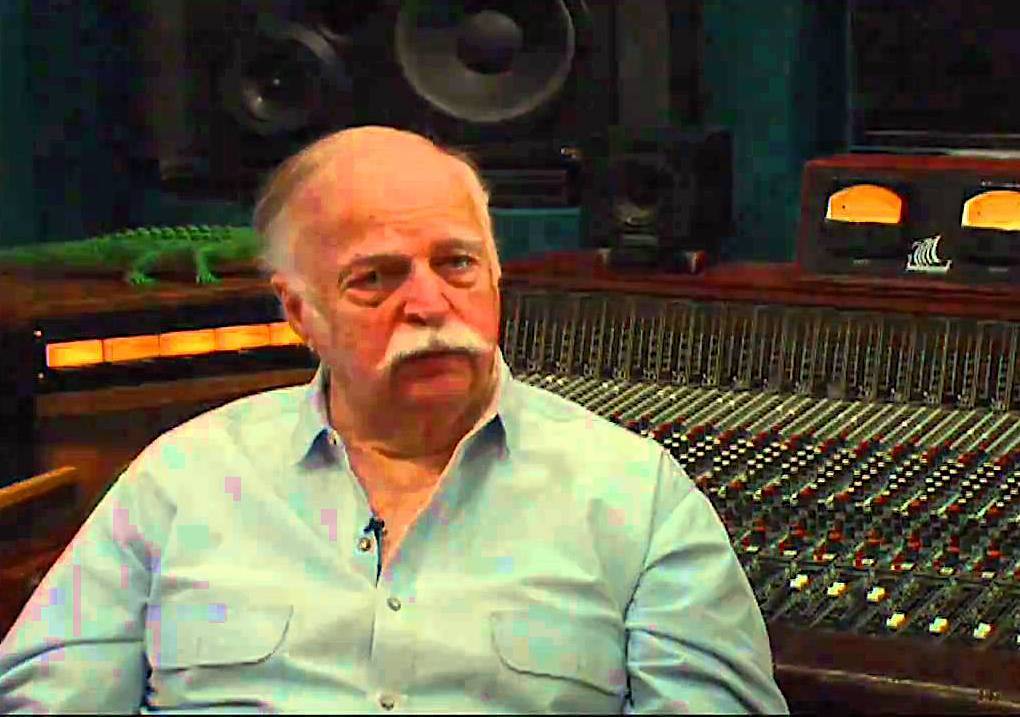

An Interview With Bruce Swedien – The Godfather Of Modern Recording

Perhaps no one else in the studio world can so aptly claim the moniker of “Godfather of Recording” as Bruce Swedien. Universally revered by his peers, Bruce has earned that respect thanks to years of stellar recordings for the cream of the musical crop. His credits could fill a book alone, but legends such as Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, Stan Kenton, Duke Ellington, Woody Herman, Oscar Peterson, Nat “King” Cole, George Benson, Mick Jagger, Paul McCartney, Edgar Winter, and Jackie Wilson are good places to start. Then comes Bruce’s Grammy-winning projects, which include Michael Jackson’s Thriller (the biggest-selling record of all time), Bad, and Dangerous and Quincy Jones’ Back on the Block and Jook Joint.

As one who has participated in the evolution of modern recording from virtually the beginning, as well as being one of its true innovators, Bruce is able to give insights on mixing from a perspective that few of us will ever have.

This interview (which appears in its entirely in my Mixing Engineer’s Handbook) was done quite a while ago, but Bruce’s insights are timeless.

Bobby Owsinski: Do you have a philosophy about mixing that you follow?

Bruce Swedien: The only thing I could say about that is everything that I do in music—mixing or recording or producing—is music driven. It comes from my early days in the studio with Duke Ellington and from there to Quincy. I think the key word in that philosophy is what I would prefer to call “responsibility.” From Quincy—no one has influenced me more strongly than Quincy—I’ve learned that when we go into the studio, our first thought should be that our responsibility is to the musical statement that we’re going to make and to the individuals involved, and I guess that’s really the philosophy I follow.

Responsibility in that you want to present the music in its best light?

To do it the best way that I possibly can. To use everything at my disposal to not necessarily re-create an unaltered acoustic event, but to present either my concept of the music or the artist’s concept of the music in the best way that I can.

Is your concept ever opposed to the artist’s concept?

It’s funny, but I don’t ever remember running into a situation where there’s been a conflict. Maybe my concept of the sonics of the music might differ at first with the artist, but I don’t ever remember it being a serious conflict.

Is your approach to mixing each song generally the same, then?

No. That’s the wonderful part about it. I’ll take that a step further and I’ll say it’s never the same, and I think I have a very unique imagination. I also have another problem in that I hear sounds as colors in my mind [this is actually a neurological condition known as synesthesia]. Frequently when I’m EQing or checking the spectrum of a mix or a piece of music, if I don’t see the right colors in it I know the balance is not there.

Can you elaborate on that?

Well, low frequencies appear to my mind’s eye as dark colors, black or brown, and high frequencies are brighter colors. Extremely high frequencies are gold and silver. It’s funny, but that can be very distracting. It drives me crazy sometimes.

What are you trying to do then, build a rainbow?

No, it’s just that if I don’t experience those colors when I listen to a mix that I’m working on, I know either that there’s an element missing or that the mix values aren’t satisfying.

How do you know what proportion of what color should be there?

That’s instinctive. Quincy has the same problem. It’s terrible! It drives me nuts, but it’s not a quantitative thing. It’s just that if I focus on a part of the spectrum in a mix and don’t see the right colors, it bothers me.

How do you go about getting a balance? Do you have a method?

No, it’s purely instinctive. Another thing that I’ve learned from Quincy, but that started with my work with Duke Ellington, is to do my mixing reactively, not cerebrally. When automated mixing came along, I got really excited because I thought, “At last, here’s a way for me to preserve my first instinctive reaction to the music and the mix values that are there.” You know how frequently we’ll work and work and work on a piece of music, and we think, “Oh boy, this is great. Wouldn’t it be great if it had a little more of this or a little more of that?” Then you listen to it in the cold, gray light of dawn, and it sounds pretty bad. Well, that’s when the cerebral part of our mind takes over, pushing the reactive part to the background, so the music suffers.

Do you start to do your mix from the very first day of tracking?

Yes, but again I don’t think that you can say any of these thoughts is across the board. There are certain types of music that grow in the studio. You go in and start a rhythm track and think you’re gonna have one thing, and all of a sudden it does a sharp left and it ends up being something else. There are other types of music where I start the mix even before the musicians come to the studio. I’ll give you a good example of something. On Michael’s HIStory album, for the song “Smile, Charlie Chaplin,” I knew what that mix would be like two weeks before the musicians hit the studio.

Where do you generally build your mix from?

It’s totally dependent on the music, but if there were a method to my approach, I would say the rhythm section. You usually try to find the motor and then build the car around it.

What level do you usually monitor at?

That’s one area where I think I’ve relegated it to a science. For the nearfield speakers, I use Westlake BBSM8s, and I try not to exceed 85dB SPL. On the Auratones I try not to exceed 83. What I’ve found in the past few years is that I use the big speakers less and less with every project.

I love the way you sonically layer things when you mix. How do you go about getting that?

I have no idea. If knew, I probably couldn’t do it as well. It’s purely reactive and instinctive. I don’t have a plan. Actually, what I will do frequently when we’re layering with synths is to add some acoustics to the synth sounds. I think this helps in the layering in that the virtual direct sound of most synthesizers is not too interesting, so I’ll send the sound out to the studio and use a coincident pair of mics to blend a little bit of acoustics back with the direct sound. Of course it adds early reflections to the sound, which reverb devices can’t do. That’s the space before the onset of reverb where those early reflections occur.

So what you’re looking for more than anything is early reflections?

I think that’s a much overlooked part of sound because there are no reverb devices that can generate that. It’s very important. Early reflections will usually occur under 40 milliseconds. It’s a fascinating part of sound.

When you’re adding effects, are you using mostly reverbs or delays?

A combination. Lately, though, I have been kinda going through a phase of using less reverb. I’ve got two seven- foot-high racks full of everything. I have an EMT 250, a 252, and all the usual stuff, all of which I bought new. No one else has ever used them. It’s all in pretty good shape, too.

How long does it usually take you to do a mix?

That can vary. I like to try not to do more than one song a day unless it’s a really simple project, and then I like to sleep on a mix and keep it on the desk overnight. That’s one of the advantages of having my little studio at home.

How many versions of a mix do you do?

Usually one. Although when I did “Billie Jean,” I did 91 mixes of that thing, and the mix that we finally ended up using was Mix 2. I had a pile of half-inch tapes to the ceiling. All along we thought, “Oh man, it’s getting better and better.” [Laughs]

Do you have an approach to using EQ?

I don’t think I have a philosophy about it. What I hate to see is an engineer or producer start EQing before they’ve heard the sound source. To me it’s kinda like salting and peppering your food before you’ve tasted it. I always like to listen to the sound source first, whether it’s recorded or live, and see how well it holds up without any EQ or whatever.

What do you do to make a mix special?

I wish I knew. The best illustration of something special is when we were doing “Billie Jean,” and Quincy said, “Okay, this song has to have the most incredible drum sound that anybody has ever done, but it also has to have one element that’s different, and that’s sonic personality.” I lost a lot of sleep over that. What I ended up doing was building a drum platform and designing some special little things like a bass drum cover and a flat piece of wood that goes between the snare and the hat. And the bottom line is that there aren’t many pieces of music where you can hear the first three or four notes of the drums and immediately tell what song it is. I think that’s the case with “Billie Jean,” and that I attribute to sonic personality, but I lost a lot of sleep over that one before it was accomplished.

Do you determine that personality before you start to record?

Not really, but in that case I got to think about the recording setup in advance. And of course, I have quite a microphone collection that goes with me everywhere (17 anvil cases!), and that helps a little bit in that they’re not beat up.

You can read more from The Mixing Engineer’s Handbook and my other books on the excerpt section of bobbyowsinski.com.