- in Production by Bobby Owsinski

Farewell And Thanks Geoff Emerick

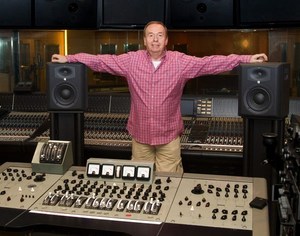

If you’re in the music business or know any of its history you probably know the name Geoff Emerick. Geoff made a name for himself as one of the original 5 Beatles engineers, then went on to a fruitful, yet often overlooked career afterwards, recording Paul McCartney and Wings, Elvis Costello, Cheap Trick, America, Ultravox and Robin Trower, among many others. Looked upon as a giant in the field, Geoff passed away suddenly on Tuesday at the age of 72.

If you’re in the music business or know any of its history you probably know the name Geoff Emerick. Geoff made a name for himself as one of the original 5 Beatles engineers, then went on to a fruitful, yet often overlooked career afterwards, recording Paul McCartney and Wings, Elvis Costello, Cheap Trick, America, Ultravox and Robin Trower, among many others. Looked upon as a giant in the field, Geoff passed away suddenly on Tuesday at the age of 72.

Geoff was an uncredited innovator and recording experimenter who was never afraid to try something in an age and situation when that was not only frowned upon, but actually cause for dismissal. Coming up in the old EMI Abbey Road system, engineers were taught the “proper” way to do things, which had worked well for classical music for decades, but didn’t quite fit with the demands of the new music of the 60s. Thanks to the encouragement and power of the biggest band in the world, Geoff was able to break those constraints to create some of the techniques that are common to recording today.

Like what, you might ask? How about close and multi-miking drums. Up until Geoff, the drum kit was recorded with a single mic overhead, and sometimes one on the bass drum. Geoff broke the EMI rules by adding a mic for every drum and cymbal and moving those mics in closer to the heads. No big deal today, but a very big one then, and one which had his bosses up in arms, but also tied up due to the Fab 4’s prominence. He was also the first engineer to place a mic inside the bass drum. Something that we do every day now but was unheard of back then.

This also applied to instrument amplifiers, which were miked from a 2 foot distance at the time (still not a bad way to do it). Geoff pushed those mics right up against the grill to get the sound The Boys wanted. His bosses freaked out as it wasn’t the EMI way to do things, but it’s a technique we still use today.

My favorite Geoff Emerick technique is using a speaker as a microphone. The Beatles wanted more low end on their records, so Geoff turned a speaker cabinet into a microphone and placed it against the bass amp. That’s the sound you hear on “Rain.” That was the precursor to the subkick mic so widely used on kick drums today. Then there’s tape reversal, flanging, high-speed recording dropped to normal speed, intentionally distorting console inputs and outboard gear, high compression, and numerous other techniques that are common today that I can’t think of at the moment.

I didn’t know him well, but Geoff was always kind to me whenever I saw him. I was always a little taken back that he remembered me and took the time to say hello. I remember meeting him on the street at a San Francisco AES show. We were both in a hurry and going in opposite directions, yet he made the first effort to reach out with a greeting. I’m still a little taken back when I think about it now.

Geoff had lived with heart problems and a pacemaker for some time, but the word is that he passed quickly, which is always a blessing. One thing I know is that we’re all going to miss him greatly. Thank you, Geoff Emerick, for all you’ve given us!