- in Book Excerpt , Production by Bobby Owsinski

How George Martin Changed The Finances Of The Record Business

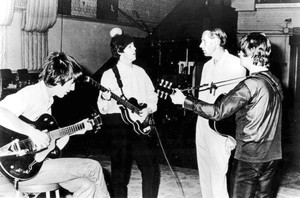

When iconic record producer George Martin passed away a few years ago it brought effusive thoughts, memories and well-deserved accolades from all quarters of the music business. Most dwelled on Sir George’s creative accomplishments, and truly there were many. Just his work with The Beatles alone changed the way we make music forever, not to mention his work with other top selling artists like America, Jeff Beck, Paul McCartney, Little River Band, Gerry & The Pacemakers, Kenny Rogers, Kate Bush and many more.

When iconic record producer George Martin passed away a few years ago it brought effusive thoughts, memories and well-deserved accolades from all quarters of the music business. Most dwelled on Sir George’s creative accomplishments, and truly there were many. Just his work with The Beatles alone changed the way we make music forever, not to mention his work with other top selling artists like America, Jeff Beck, Paul McCartney, Little River Band, Gerry & The Pacemakers, Kenny Rogers, Kate Bush and many more.

But an unsung Martin contribution to the music business is the way he changed the finances of making a record. And, as sometimes happens with many giant changes that occur, it has been to the betterment of some and at the expense of others.

Early Career

Martin’s career as a producer began in 1950 when he joined EMI Records as an assistant to Oscar Preuss, the head of EMI’s Parlophone Records. When Preuss retired in 1955, Martin took over as head of the label, which at the time specialized in classical and Baroque music, original cast recordings, and regional British music, and was a rather insignificant subsidiary of the company.

Martin turned the sleepy division into a moneymaker though, by concentrating on comedy and novelty records by the likes of Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan, Dudley Moore and Peter Cook, among others, but it wasn’t until he signed The Beatles that the label hit gold – vaults of it. The band went on to sell hundreds of millions of records worldwide and reap EMI record-setting profits within a very short period, but Martin was still only a salaried employee with no participation in the profits he had such a big part in developing, which was a common trait of record producers of the time.

The Straw That Breaks The Back

In 1969, after being passed over for a small bonus even though The Beatles had made EMI another year of historic profits with a succession of #1 worldwide hits, Sir George decided to use his considerable leverage to obtain a piece of the action by leaving his EMI staff position and going his own way. Soon many other successful producers followed, finally starting to cash in on large advances as well as receiving a piece of their best-selling artist’s pie.

The Labels Respond

But fortunes turned, as they so frequently do. After a while, record labels began to see producer independence as a bargain, because they were able to wipe out the overhead of a salaried position by turning the tables so that hiring the producer became the artist’s expense instead of the label’s. This meant that the label could afford to have the best production talent in the world, yet in the end it wouldn’t cost them a dime as long as the record sold. The artist was stuck with the expense of not only the producer’s advances, but his royalty as well, which could be as much as a quarter of the artist’s total royalty.

No one could ever begrudge Martin for taking the bold move to become an independent producer in order to take financial advantage of the enormous cash cow he had spearheaded. He definitely earned it, but in doing so, he blazed a trail for all producers and artists thereafter. Most producers today are independent as a result, and most artists bear the brunt of the costs of hiring the producer. As is usually the case, except for a very few successful producers, the record labels were the winners in the end.

The Producer’s Role Expands

As time went on, the music producer took more creative control in the record making process, becoming everything from a coach to a guidance counselor to a psychiatrist to a Svengali, production characteristics pioneered by Martin himself.

Some producers like Holland-Dozier-Holland at Motown and Stock, Aitken, and Waterman in the United Kingdom used a factory approach, where the artists were interchangeable and subordinate to the song. Some, like Phil Spector and Brian Wilson, had a grandiose vision for their material that only they could imagine until it had been completed. Some, like Ted Templeman, Tony Brown and Dann Huff, Moby, Dr. Dre, and Max Martin changed the direction of a style of music. And others, like Quincy Jones, saved the music industry from itself and started the longest run of prosperity it would ever see, but all would owe their independence and good fortune to the vision of Sir George Martin.

Some of the above is an excerpt from The Music Producer’s Handbook. You can read more from The Music Producer’s Handbook and my other books on the excerpt section of bobbyowsinski.com.